To Stretch or Strengthen?

Let’s start with a quick scenario. You are a typical adult, just trying to live a well balanced life between your own health, spending time with your family, and your work. You know the importance of a good diet, getting adequate sleep and exercising regularly. You also have a spouse and two young children who require much of your time. So you wake up early, get your kids ready for school, head to work, come home and eat a healthy dinner with your family, get the kids ready for bed, then head to bed yourself (maybe you sneak a beer in there too). The only time you have to squeeze in there for exercise is for 30 minutes during your 60 minute lunch break so you can still eat.

Only 30 minutes, you have to make the most of each minute but what do you prioritize? Flexibility? Strength? Cardio? Maybe you can do some of each but that doesn’t give you much time. On top of that you’ve heard that if you strengthen you’re also going to become tight and less flexible, so you have to mix in some stretching right?

Well, maybe this isn’t actually the case. What if I told you that you could cut out the time stretching and spend more time on strength and cardiovascular training while not losing any flexibility and maybe even improving it, by stretching while strengthening? Some people are just born more flexible than others and yet flexibility can still be increased through training.

So what happens when we stretch and how do we truly increase our muscle length?

What Happens When We Stretch?

I want to start by saying that the effects of stretching at the microscopic level within the muscle cells is still not fully understood. There are multiple theories out there as to what is going on within the muscle and how muscle length is increased. At the risk of getting too into the weeds I will just give a (semi) quick description of muscle physiology and hopefully leave it at that.

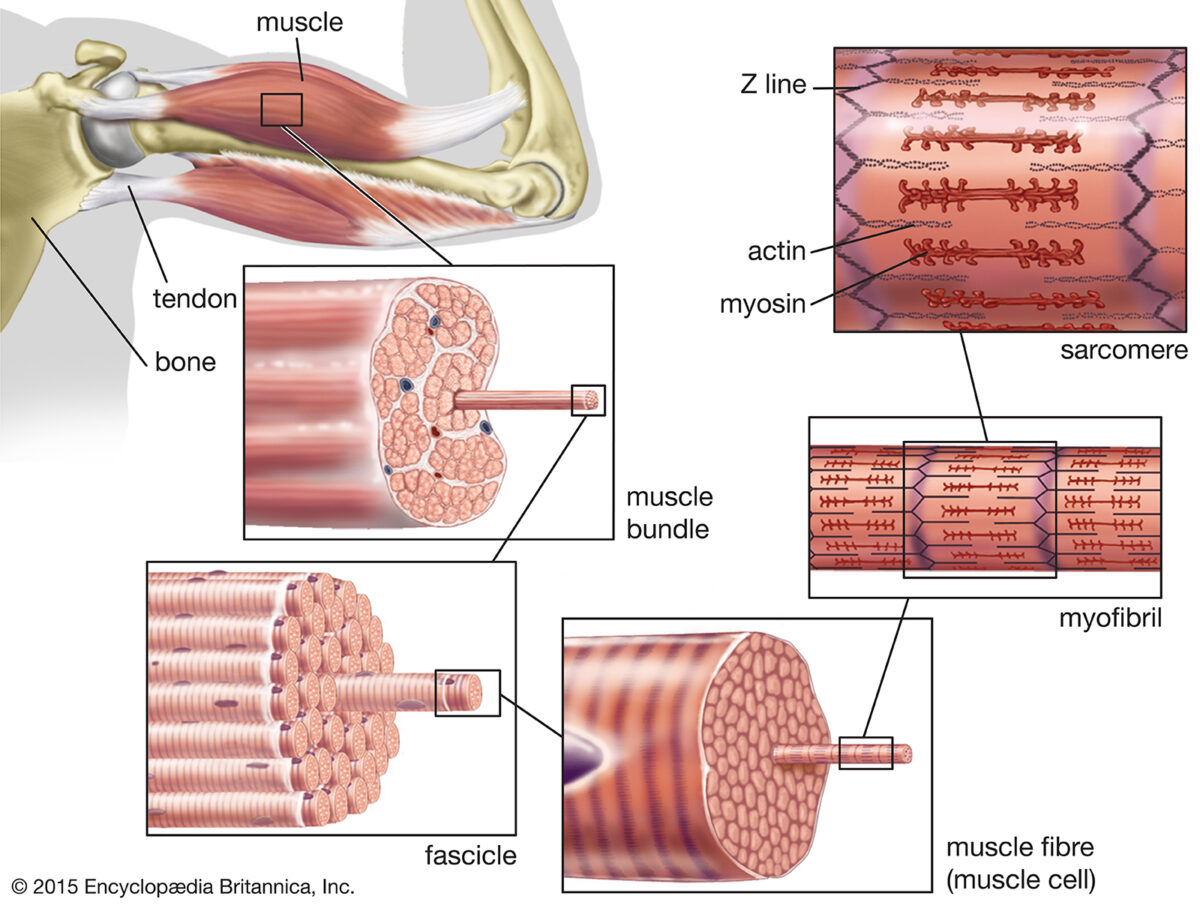

Each muscle is actually many complex components added up to make it so you can lift your coffee cup to your mouth or stand up from a chair. Each muscle is made up of many fascicles composed of groups of fasciculi which are made up of many individual muscle fibers. Muscle fibers are still made up of thousands of tiny strands called myofibrils responsible for contracting, relaxing, and lengthening.

Now we’re still not done; each myofibril is made up of contractile units laid out end to end called sarcomeres. Each sarcomere has thick (myosin) and thin (actin) myofilaments that overlap. When the filaments pull towards each other they contract and when they move away from each other they relax. When billions of sarcomeres shorten at the same time a muscle contraction occurs.

Complex huh?

Just think of one of those huge ropes that hold giant ships to the harbor. If you look closely, those ropes are made up of many smaller ropes made up of many smaller strands made up of individual fibers. Now just imagine this rope

shortening and elongating, it all starts with the individual fibers.

What seems to be agreed upon is that when a muscle is stretched, the thick and thin filaments in the sarcomere move further apart and the sarcomeres within each myofibril move until they are end to end, resulting in a longer muscle fiber and therefore longer muscle.

However, studies show that following a passive stretch, the sarcomeres and thick and thin filaments go back to their starting position which is set based on the demands of that muscle. This is because there is an optimal amount of overlap of thick and thin filaments within the sarcomere that give the best and strongest contraction. This means that static stretching probably doesn’t have the lasting effect that we thought it did.

This tracks with current research that shows increases in muscle length, measured by looking at the increase in range of motion a joint can move through as transient. If you spend 5 minutes reaching towards your toes, your going to be able to reach further at the end of the 5 minutes than when you started, so your muscle got longer right? Well, when you try again a few hours later, or maybe the next day, you are probably only going to be able to reach as far as the first time you tried.

One of the more recent theories on muscle elongation says that the improvements in range of motion isn’t because you are truly permanently increasing your sarcomeres in a series and therefore myofibrils->muscle fibers->fascicle->fascicles and the entire muscle, but actually because you are altering sensation. It appears that muscle stiffness is a continuously adapting property of skeletal muscle, adjusting day to day to the experienced range of motion.

Passive stretching has been shown to alter and decrease muscle stiffness through stimulating your nervous system and essentially desensitizing it to allow for more “stretch pain” to be tolerated. This is why when you stretch, your flexibility gains tend to be short lived, research shows that these effects only last a few hours up to a day (if done consistently and regularly).

How Do We Increase Muscle Length?

Again, the science behind this topic isn’t all there yet but there seems to be some pretty good evidence that an active component is required.

This means that while passive or static stretching may increase range of motion in the short term due to changes in sensation and pain tolerance, actually increasing the length of the muscle in the long term requires you to contract that muscle at some point during the stretch.

One theory as to why has to do with calcium dependent pathways being required to regulate the number of sarcomeres in a series, something that only happens with an active contraction of the muscle. This goes back to what was mentioned before, that muscles adapt to the demands placed on them. So if you give the muscle a task that requires it to contract in a lengthened position, that muscle will have to adapt (lengthen) to do so.

Strength Training Or Stretching?

There is evidence to show that muscle contraction is required to increase muscle length, and I think it’s obvious to say that it is also required to increase the strength of a muscle, why not spend that time stretching strength training instead? Let’s face it, life is short and time is valuable. So if you are even remotely like the person I posed in my scenario earlier, why not make the most of your time and kill 2 birds with one stone?

One preliminary study compared 3 groups over the course of 5 weeks. One group completed a full range of motion resistance training program, one completed a static stretching program, and the control group did neither.

They measured the range of motion and strength of the joints and muscles being worked out for all 3 groups before, during and after the program. Not surprisingly they saw a significant improvement in strength in the resistance training group compared to the other two groups.

But they also found that both the static stretching group AND the resistance training group significantly improved range of motion AKA became more flexible.

Just think about yoga. Yogi’s tend to already be very flexible people, but someone who just started yoga can improve their flexibility over time. I like to think that a lot of the flexibility improvements is because yoga is active and not passive, and if you think it is then you clearly have never done it, it’s HARD! It requires constantly moving through poses and holding positions using your muscles through their entire range of motion placing new active demands on your muscles and forcing them to adapt to new ranges over time.

How I Use Static Stretching

Now, I’m not saying that traditional static stretching is a waste of time (all of the time). As a physical therapist I prescribe stretches quite often, and even do them myself a good amount.

Sometimes a muscle is incredibly tight or irritated following an injury or because you’ve been sitting for 5 hours, stretching might be just what you need to increase comfort so you can work for the next 5 hours.

However, I try to educate all of my patients that static stretches are more for comfort and getting you through the moment. But if we want to make real changes to not just strength but also muscle length and flexibility, then our time is better spent on active movement and strengthening through the entire range of motion of that muscle.

So the next time you only have 30 minutes to work out, instead of spending 10-15 minutes stretching add in some full range of motion resistance training instead. Research has shown that eccentric contractions (the activation of a muscle as it is lengthening) is the best way to change the architecture of a muscle and increase its length, however for the sake of simplicity I think that controlled full ROM

exercise will meet your needs.

Hamstring Program

Instead of just talking about it I’ll give some examples that research has proven to work.

The following are 2 exercises for the hamstrings, a muscle group that is often a source of tightness and frustration for a lot of people. Both of these exercises have the added benefits of reducing incidence of hamstring injuries.

1. Nordic Hamstring

● Begin in the tall kneeling position with your feet pointing straight back and your hips and back locked into place.

● Your feet will need to be placed under a sturdy object in order to resist your weight as you are lowering your body towards the ground.

● Slowly begin controlling your descent towards the ground (slow and controlled is key) resisting gravity.

● Lower yourself as far as possible before letting gravity win and helping support yourself with your arms.

● From there try and pull yourself back to the starting position using your legs (you may need the assist of your hands)

● Complete 2-3 sets of 6-10 reps 2-3 days per week

This is a challenging exercise and may require modifications for some people. If you would like to see some variations of this exercise or ways to set it up at home ill put a link to a youtube video by E3 rehab for some good ideas on modifications. Keep in mind that unless you are completing the full exercise you may not be making as much change in hamstring length, but these variations may help you build up to completing the full exercise.

2. Askling Glider Exercise

● Start with the trunk upright, one hand holding on to a support and legs slightly apart.

● All body weight should be on the heel of the front foot with the knee slightly bent (approx. 10-20deg

● Begin by gliding backward on the back foot until the end of the range is reached due to either pain or tightness(you’ll need a low friction surface such as a sock, towel, or slider)

● The movement back to the starting position should be performed by the help of both arms, not using the front leg.

● To progress, increase the gliding distance and perform the exercise faster.

● Complete 3 sets of 4 reps 3 days per week.

For video reference I will link a youtube video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UU8pRuYL4b4

Sources

Afonso, J., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Moscão, J., Rocha, T., Zacca, R., Martins, A., . . . Clemente, F. M. (2021). Strength training is as effective as stretching for improving range of motion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. doi:10.31222/osf.io/2tdfm

Marušič, J., Vatovec, R., Marković, G., & Šarabon, N. (2020). Effects of eccentric training at long‐muscle length on architectural and functional characteristics of the hamstrings. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(11), 2130-2142. doi:10.1111/sms.13770

Riley, D. A., & Van Dyke, J. (2012). The effects of active and passive stretching on muscle length. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 23(1), 51-57. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2011.11.006

Weppler, C. H., & Magnusson, S. P. (2010). Increasing muscle extensibility: A matter of increasing length or modifying sensation? Physical Therapy, 90(3), 438-449. doi:10.2522/ptj.20090012

Physiology of Stretching. STRETCHING AND FLEXIBILITY – Physiology of Stretching. http://www.mit.edu/activities/tkd/stretch/stretching_2.html. Accessed April 8, 2021.

Daniel Betz, DPT

This post was written by Dr. Daniel Betz in August of 2021.

Learn more about Dan on our about page: https://gopt.co/about/