Within the last few decades, climbing has increased in popularity and become a mainstream activity!

Coupled with its boom in popularity, the incidence of climbing-related injuries has also increased. In a review conducted by Jones et. al, they found that climbing injury prevalence amongst climbers ranged from 10% to 81%.

Climbing requires individuals to repeatedly practice challenging moves at their maximal capacity. These moves require increased loading of the upper extremities and unique contortion of the lower extremities (ie drop knees).

Climbing injuries can be classified as:

- Acute impact injuries

- Acute non-impact injuries

- Or chronic overuse injuries.

Overlap within the different categories is also not uncommon.

Types of Climbing Injuries

Impact Injuries

Most lower extremity injuries in climbers can be attributed to falling or jumping off the wall, with beginners having a greater risk of injury to the lower extremities. In a literature review from Jones et. al, they found that…

…of all climbing-related injuries, 10-50% of those were impact injuries.

The best way to avoid impact injuries is to downclimb or fall as safely as possible. Falling safely includes clearing the mat beneath the area you will be climbing over to avoid falling on people/objects.

If you are falling, land with your feet wide and chin tucked, on impact let your knees bend, and then roll onto your back or side. Do not try to catch yourself with your hands or stick the landing.

Seattle Bouldering Project offers an introductory course for new climbers which covers falling safely.

Non-impact Acute Injuries

Non-impact acute injuries occur due to acute trauma to the body. This can include muscle strains and/or tendon ruptures.

Chronic Overuse Injuries

Jones et. al found that approximately 33-44% of climbing injuries are due to chronic overuse. Chronic overuse injuries are caused by repetitive use of a body region (musculotendinous unit or joint) during sport or activity. Chronic overuse injuries, in climbers, often present as tendinopathies.

Common Climbing Injuries

Annular (A) Pulley Injury

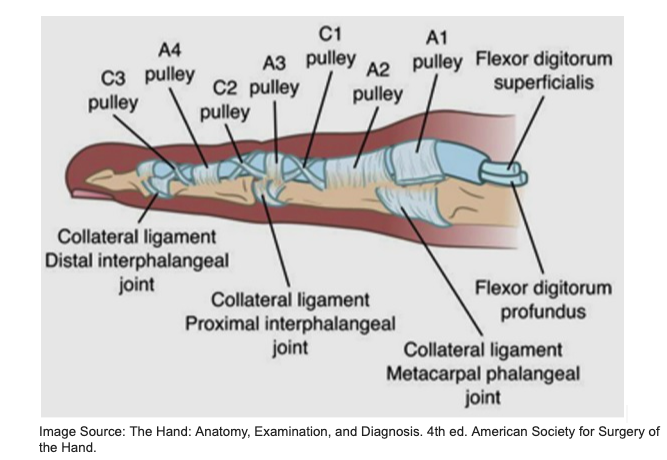

Injuries to the fingers are the most common injury, accounting for 33-52% of all climbing related injuries. A2 pulley injuries are one of the most common injuries in boulderers. As seen in the image above, a series of pulleys per finger help keep the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) from bowstringing or pulling away from the bone when the fingers are flexed.

The FDP plays a major role in grip while climbing. When the strength threshold of the pulley is exceeded, it can be injured. Injuries may range from a strain to a single pulley rupture to multiple pulley ruptures. Annular pulleys are subjected to increased forces during crimping position. The A2 pulley has the greatest likelihood of rupture, because the crimping position creates significant stress on the A2 pulley. With great enough force, additional pulleys can rupture as well. A2 pulley injuries may also result from overuse/overtraining.

While projecting or climbing, climbers may consistently be trying moves near the threshold of annular pulley tissue strength. Without adequate rest between attempts, this may reduce the integrity of the tissue. Otherwise, overtraining can occur when there is not adequate rest for regeneration of the tissue.

A2 pulley injuries can occur off the wall or rock when climbers do not rest adequately during and/or after a hangboarding session.

Hangboarding protocols typically advise 48-72 hours of recovery between sessions.

Subacromial Pain

The shoulder is the second most common location for climbing related injuries accounting for 17% of injuries. These shoulder injuries are often due to structures located in the subacromial space (shown in the image below) becoming aggravated and inflamed. Structures located in this space include bursae, long head of the biceps tendon, supraspinatus tendon, and subscapularis tendon. This injury is typically due to repetitive poor positioning between the scapula and the humerus.

Climbers often find themselves in these aggravating positions because of deficits in shoulder strength, mobility, and coordination. For example, It is common for boulderers to overdevelop their shoulder internal rotator musculature, which can cause imbalances with the stabilizing shoulder external rotators, resulting in humeral elevation and compression in the subacromial space.

SLAP Tear

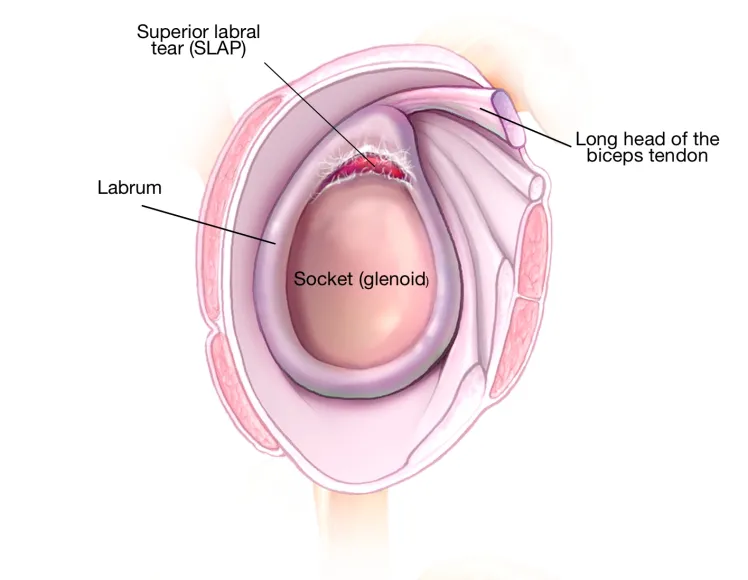

Superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) tears are another common shoulder injury that climbers sustain. The shoulder, or glenohumeral, joint is a ball and socket joint with the glenoid fossa of the scapula acting as the socket and the head of the humerus serving as the ball. The labrum is a fibrocartilaginous structure that encircles the rim of the glenoid fossa of the scapula to provide additional support and stability to the head of the humerus.

A SLAP tear occurs when the labrum is pulled off of the glenoid. More specifically it occurs at a region between 12pm-3pm, if you imagine your shoulder like a clock. These tears can occur over a long period of multiple micro tears, or from a single traumatic event.

The mobility of the shoulder that is essential for climbing can put the joint at increased risk for injury. SLAP tears can fall under all three categories of climbing related injuries. They can occur as an impact injury due to a fall onto an outstretched arm. Or it could happen “acutely” if a climber reaches for the next hold and loses their footing, and their full body weight is unexpectedly put through one arm potentially leading to a partial or full-thickness SLAP tear. These tears may also occur when climbers perform dynos if they catch the holds with completely relaxed shoulder muscles.

Climbing Injury Prevention Strategies

Training volume/load management

Injury prevention begins off the wall with focus on appropriate sleep, hydration, and nutrition. Adequate rest encompasses both rest between attempts and training sessions.

It is also important to vary the route types you are climbing.

There is a tendency to naturally gravitate towards our strengths and avoid our weaknesses (ie slabs vs overhangs). It will make you a more well rounded climber and help reduce risk of developing overuse injuries by creating muscle imbalances.

Warm-Up

The beginning of the climbing session should be devoted to warming-up both on and off the wall. Deliberate warm-ups can help improve climbing performance and reduce risk of injury.

Shoulder Strengthening for Climbing

Scapular retraction with shoulder external rotation

Strengthens antagonists of shoulder internal rotators.

- Hold a resistance band in both hands with your elbows bent to 90 degrees and your palms facing up

- Squeeze your shoulder blades together and rotate your arms out to the side

- Slowly return to the starting position

Serratus anterior shoulder flexion

Strengthens the serratus anterior which works with the lower trapezius to produce upward rotation of the scapula necessary for scapulohumeral rhythm.

- Begin with a resistance band around your wrists, palms facing inwards, forearms parallel, and elbows bent to 90 degrees

- Keep your arms shoulder width apart and raise them overhead

- Slowly return to the starting position

- Make sure to keep your forearms parallel to each other

D2 flexion

Strengthens lower trapezius and shoulder external rotators.

- Start holding a resistance band in both hands

- One hand will stay by your side, maintaining tension in the band. The other hand will start with the thumb pointing in towards the hip

- Raise your arm in a diagonal motion, rotating your forearm so that your thumb is pointing up

- Slowly reverse the motion and return to the starting position

Standing Y’s at the wall

Strengthens the lower trapezius in an overhead position.

- Begin with both arms overhead in a “Y” position resting against a wall

- Squeeze your shoulder blades down and in together to raise your arms off the wall

- Slowly lower them back to the wall

Hand/Wrist Strengthening for Climbing

Tendon glides

Can help warm-up muscles in the hand and wrist and improve dexterity and mobility.

- Start with your hand open

- Keep your fingers straight and bend at the first finger joint

- Return to start

- Bend at the first and second joints to make a loose fist

- Return to start

- Bend at the second and third joints to bring your fingertips to the top of your palm

- Return to start

Finger rolls with wrist flexion

Strengthens wrist and finger flexors for improved strength and stability.

- Start by holding a weight in your hand with your palm facing up

- Slowly lower the weight and let it roll down your fingers without dropping it

- Curl your fingers and wrist to lift the weight back up

Wrist extension with eccentric lowering

Strengthens wrist extensors for improved strength and stability.

- Hold a weight in your hand with your palm facing down

- Bend at your wrist and lift the weight up

- Very slowly lower the weight down

Dumbbell pronation/supination

Strengthens wrist for improved strength and stability.

- Start with your elbow flexed to 90 degrees and by your side, holding the end of a dumbbell in one hand

- Slowly rotate your forearm until your palm is facing the floor

- While keeping your wrist straight, slowly return to the starting position

Emma Pahl DPT

This post was written by Dr. Emma Pahl in October of 2022.

Learn more about Emma on our about page: https://gopt.co/people/freemont-staff/emma-pahl/

References

- Jones G, Schöffl V, Johnson MI. Incidence, Diagnosis, and Management of Injury in Sport Climbing and Bouldering: A Critical Review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2018;17(11):396-401. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000534

- Jones G, Johnson MI. A Critical Review of the Incidence and Risk Factors for Finger Injuries in Rock Climbing. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016;15(6):400-409. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000304

- Auer J, Schöffl VR, Achenbach L, Meffert RH, Fehske K. Indoor Bouldering-A Prospective Injury Evaluation. Wilderness Environ Med. 2021;32(2):160-167. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2021.02.002

- Schweizer A. Sport climbing from a medical point of view. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13688. Published 2012 Oct 11. doi:10.4414/smw.2012.13688

- Rayan, G. M., & Akelman, E. (2012). The hand: anatomy, examination, and diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.